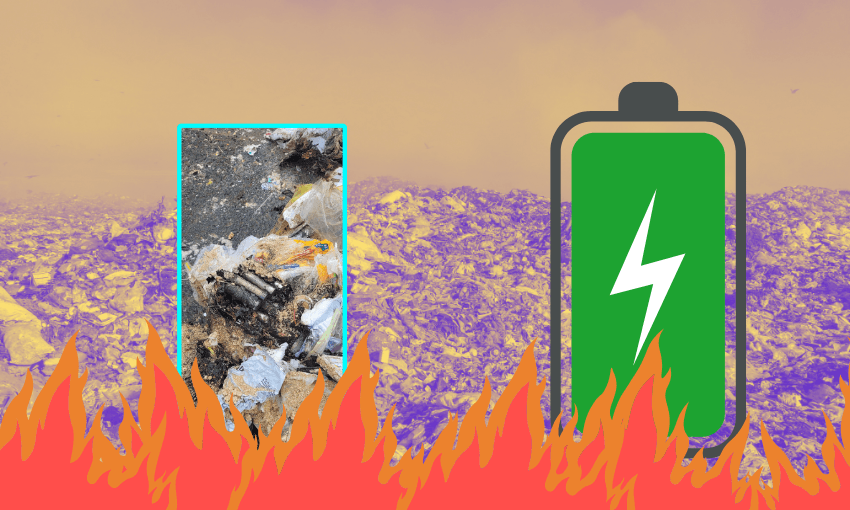

When batteries end up in the general waste, they can cause fires, putting people and property at risk and damaging the environment. Shanti Mathias investigates why disposing of batteries is so complex – and so expensive.

When a rubbish truck catches fire, smoke twirling out over the road, the safety procedure is immediate: the driver needs to dump the entire contents of their truck on the kerb and wait for Fire and Emergency to deal with it. These smoking piles of rubbish are a massive human health and environmental risk.

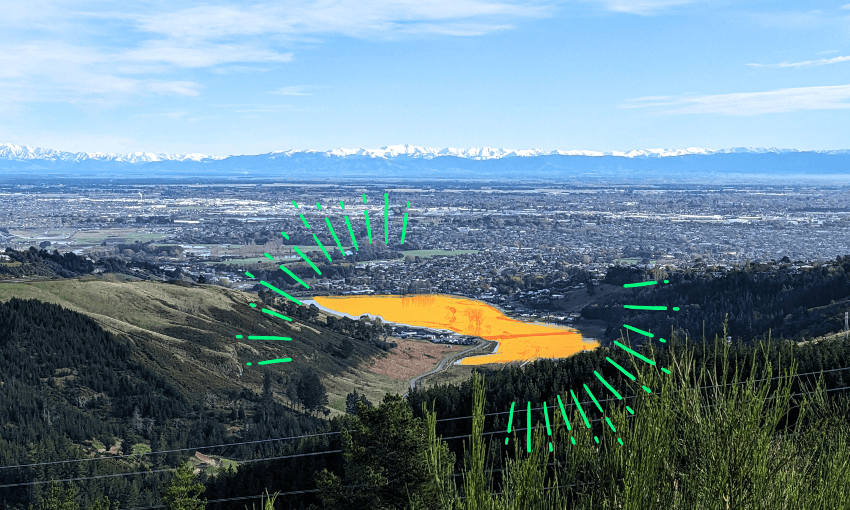

Rubbish truck fires are most often caused by one thing: batteries. And battery-sparked fires are becoming more common, with 13 in Auckland in 2025 so far, and five in Christchurch, compared to 20 and 16 in all of 2024 respectively. Auckland Council’s Waitākere Refuse and Recycling Transfer Station in Henderson and the Materials Recovery Facility in Onehunga also have about two small smoulder fires a week, likely caused by batteries. While Wellington City Council hasn’t recorded any fires so far this year, there were two rubbish truck fires in Kāpiti in 2024. While it’s not always possible to trace the exact cause of a fire, and it’s likely that some aren’t noticed or recorded, batteries are the most likely culprit.

The most recent fire was last week, on Auckland’s North Shore, when a massive blaze likely sparked by a lithium-ion battery igniting destroyed the Abilities Group recycling plant, sending clouds of thick black smoke into the sky so large they were seen across the city, and prompting emergency alerts to be sent to North Shore residents warning them to stay inside.

Fires can have further implications for waste companies, too: just this week, Auckland District Court imposed a $30,000 fine on a scrap metal recycler after a battery fire in 2023 released toxic smoke that blew across the city. There is no easy way for scrap metal recyclers to detect batteries in scrap material, but Auckland Council, which brought the charges, said the case was “an important precedent in balancing empathy for emerging challenges with the necessity of regulatory compliance”, highlighting the importance of “proactive risk management”.

There are more batteries in our houses than ever before, thanks to the affordability of cheap, lithium-ion battery-powered electronics. “In my own house, we each have a phone, maybe a few in a drawer, iPads and laptops, remote controls for the TV,” says Nic Quilty, CEO of industry group WasteMINZ. Kids’ toys, handheld powertools, kitchen gizmos, all containing batteries.

Vapes are a particularly big issue; although all vapes sold now are technically rechargeable, low prices mean that many are treated as single use. Millions of vapes being sold and used around the country present a big problem. “They’re fully contained units – you can’t separate the battery out,” says Ross O’Loughlin, a regional manager at Waste Management (WM), the country’s biggest waste management provider, based in Wellington. Many phones are designed with non-removable batteries too, so those batteries are processed through e-waste systems.

As in houses, so in rubbish bins: lots of batteries, dangerously, end up in the rubbish because people don’t know where else to put them. But all the chemicals, particularly lithium, which produce a reaction inside the battery are still there, and if a battery gets dented or starts leaking, that energy can be released.

This presents a huge risk for councils, which are responsible for waste around New Zealand: fires on trucks and at recycling and waste-processing stations can harm workers and damage important infrastructure. Most councils around the country have separate battery-recycling facilities in an attempt to prevent batteries from being put into kerbside recycling or rubbish. But the systems are different depending on where you are: batteries can be dropped off at some council facilities, and some privately run ones. In certain areas, like Taranaki, there is a charge if you’re recycling batteries from a commercial business, or if you have more than 5kg of batteries.

How to recycle a battery

“We have to identify the batteries that present an immediate risk,” says O’Loughlin. Waste Management is one of a handful of companies that accepts batteries from councils or privately run battery drop-offs and has permission from the Environmental Protection Authority to ship them overseas to battery-recycling facilities. It recycled 15 tonnes of batteries last year.

If lithium gets out of a lithium-ion battery, it immediately starts reacting with the air, producing hydrogen. Those dented, deformed batteries are too dangerous to be shipped, so they have to be sealed then put in landfill. This is often done by putting the leaking batteries in a drum and pouring concrete over it so they don’t keep reacting.

The batteries that are appropriate to ship are first sorted into different types – lead car batteries are a completely different category to lithium-ion batteries like those in phones – and then packed for transport. This means individually taping over the terminals of batteries with electrical tape so they can’t ignite, then packing them in steel drums. The batteries have to be surrounded by a heat-absorbing material that can’t be set on fire; WM uses either sand or vermiculite, a natural compound which is lighter than sand. “We need to prevent a runaway reaction in the container,” O’Louglin explains.

The safety precautions are part of the shipping company’s requirements; fires in trucks are bad, but fires on ships are even worse, as simply stopping and piling rubbish onto the kerb isn’t an option. WM’s batteries are shipped to Australia, where the metals inside can be harvested for re-use: mostly nickel, cobalt and lithium. Despite all these precautions, it’s still common for there to be fires at the battery-recycling facility, due to the number of highly reactive chemicals. Other battery recyclers, including Phoenix Metalman, ship their batteries to recyclers in Korea and Japan.

There’s a host of other practical challenges that go with recycling batteries. One is insurance; when Mitre 10 introduced battery drop-off centres to its stores, the risk of fires meant it had to check with its insurer as well as Fire and Emergency New Zealand. O’Loughlin says that the cost of insurance, as well as the smaller scale, is one thing that would make it difficult to have a battery recycling facility in New Zealand. Batteries are also heavy to transport; boxes used for drop-off can’t be too large or they become impossible to move.

This process is, of course, expensive – much more so than dealing with the kinds of waste that don’t burst into flames, like cardboard. It’s expensive when a rubbish truck catches fire, with local government footing the bill, but up-to-standard battery recycling is expensive too.

So what should we do with them?

“When batteries end up in general rubbish or recycling, they can be unintentionally squashed, compacted, punctured, and when that happens they get hot and that causes fires,” Quilty says. It’s reasonably safe to keep undamaged, non-modified batteries in your house until you can get to a battery specific waste drop-off, at a Mitre 10 or Bunnings store, council-run landfill or other facility. WasteMINZ has compiled a map of battery drop-offs around the country that you can view here.

One of the reasons battery recycling differs between councils and parts of the country is that there is no national standard for what should happen to used batteries. “We have nothing from the [central] government saying ‘this is what you do with your batteries,” says Quilty. “We have no consistent national campaign.” The standardisation of recycling rules around the country has had a tangible difference and already meant less contamination of waste streams, O’Loughlin says. Clear messaging around disposing of batteries, no matter where you are, could have the same effect, and prevent some of the dangers batteries create.

“Product stewardship” is the concept of looking after an item through its whole cycle of being manufactured, used, recycled and disposed of. Quilty thinks a national product stewardship model for batteries could be implemented by the government, along with a model for e-waste.

It’s a principle that retailer Mitre 10 has applied in including battery drop-off stations in 16 of its stores around the country, funded by both the company and local councils. “We sell batteries to the New Zealand public, they’re hard to dispose of safely – we need to take ownership of that,” says Julie Roberts, Mitre 10’s head of sustainability. Mitre 10 accepts any of the types of batteries it sells for tools and handheld devices, but not other kinds of batteries like EV car batteries or solar units. “As a company, we have an obligation to be responsible for the products we put into the market,” Roberts says. Mitre 10 conducts regular desk audits of the type of batteries it’s receiving, keen to avoid the perception that it’s simply greenwashing.

The Warehouse Group, including Noel Leeming and Warehouse Stationery, offers similar e-waste and battery recycling at some of its stores, as does Bunnings. Jason Bell, chief operating officer of Noel Leeming, said in a statement that Noel Leeming and Warehouse Stationery had recycled 168kg of batteries and e-waste in 2024. Mitre 10 said it has recycled 27.5 tonnes of batteries since its programme began in 2022 and Bunnings has recycled 110 tonnes since it began accepting batteries in late 2021. E-waste programmes like TechCollect also deal with rechargeable batteries, which in some cases need to be separated from the device for battery-specific processing.

But for lots of people, the thought of fires and hazardous chemicals isn’t on their mind when they’re putting a dead battery-powered device or flat batteries from the TV remote or a kid’s toy in the bin. Councils put out lots of communications about what to do with batteries in their areas and most transfer stations have a clearly labelled battery disposal area. But only so many people regularly go to landfills or hardware stores, and many never open the council emails in their inboxes. More awareness is needed. “People need to know what to do with batteries – that’s where the risk sits,” says Roberts. “If we want a circular economy, everyone has a role to play.”