Nina Sanadze is a succinct, yet impactful, survey of the Soviet-born Melbourne-based artist by curator of Contemporary Art NGV, Amrita Kirpalani.

It consists of six large-scale installations that occupy one of The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia’s level three gallery spaces, and begins as soon as visitors approach the exhibition’s entrance.

Monuments and Movements (2019) guards the doorway with steel silhouettes that reference imperial sculptures, casting a literal shadow on the rest of what visitors are to encounter. Simultaneously, Sanadze purposefully challenges the authoritative stance of these monuments by replicating only their bare skeletons and placing them on wheels.

This interplay of gravitas and humour threads throughout the show. A visual parallel can be made with Head Under the Bed (2023), featuring what Sanadze calls ‘a minimalist depiction of a bed, a side table, two shelves and a window’ with steel, and the original 165 year-old marble head of Russian emperor, Alexander II (1818-1881) by sculptor Peter Clodt von Jürgensburg (1805-1867) casually strewn on the side.

Sanadze offers a piece of personal history for the work, which was inspired by an actual event during her stay in Georgia with the family of Georgian sculptor, Valentin Topuridze. In Head Under the Bed, what was once worshipped as part of a public monument has now been reduced to intimate domesticity, appearing even comical in the accompanying photograph of the family room where it was rediscovered by the artist. The installation itself is intentionally located in a partly hidden space, prompting visitors to discover and slowly make sense of what is presented before them. Even those unfamiliar with Soviet history will pick up on the juxtaposition, and the kind of ideology it dismantles.

The artist further interrogates this sense of “things may not be as they appear” in Bollard City (2018), which together with Apotheosis (2021), forms a strong visual impression at the very beginning of the exhibition.

Bollards and barriers that seem weighted and dignified are in fact constructs of lightweight, recycled materials such as cardboard and polystyrene. And yet they nonetheless pose as barriers to our mobility and, in some instances, ignite dreadful memories of anti-terror barriers around the world – objects so much a part of everyday life in major cities now that our eyes have learned to ignore them and our bodies navigate them on autopilot. Inside a gallery context, Sanadze cranks up our awareness to investigate and question the trade-off between public safety and personal freedom.

Deeper into the gallery, visitors will come across Call to Peace, Anatomy of the Dream (2023), where different iterations of Topuridze’s recreation of The Winged Victory of Samothrace are captured in varying states of completion, before finally arriving at Hana and Child (2023).

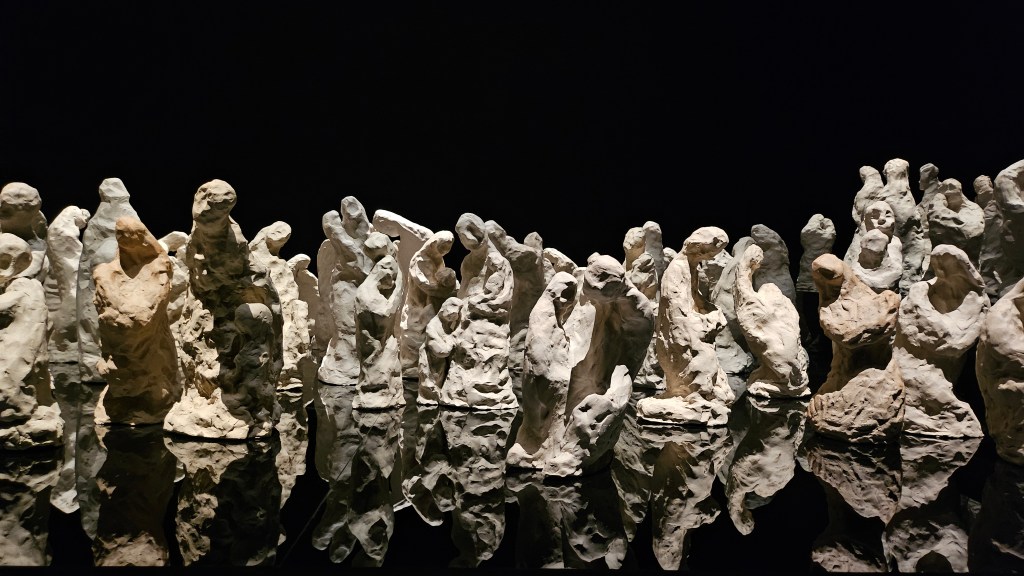

As much as Hana and Child is a sculptural installation, it is also an archive of emotions and mark-making, with hundreds of clay figures shaped with visible imprints of the hand that simultaneously speak to care, love, hope, despair and protection.

The piece was inspired by the Ivanhorod Einsatzgruppen photograph captured during WWII, depicting the murder of Jewish civilians in Ivanhorod, Ukraine where a mother clings to her child, and nearby, a soldier aims with his rifle.

The exhibition didactic informs viewers that Ivanhorod is ‘a town less than 50 kilometres from where the artist’s maternal great-grandmother, Hana, along with three of her children, was murdered by the Nazis’. Light is cast on the installation, so that the shadow of each sculpture is reflected onto the ceiling – like little floating ghosts they hover, waiting for justice, or even sympathy.

It’s an arresting ending to the exhibition despite the bleakness of its subject, and the state of the world referred to by the artist since work on the exhibition began in August 2023.

Read: Exhibition review: Dreamscape, Off the Kerb gallery

Sanadze’s sculptures and installations have been regularly spotted in group shows and prize exhibitions in the past few years, but to see them accumulated on this scale takes the experience to another level. It’s a generous show for both the artist and its viewers that encourages thoughtfulness, connection and contemplation.

Nina Sanadze is on view at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia until 4 August; free entry.